How Liberalism Requires State Neutrality Towards Morality (POSTLIB 2)

David Johnston on Liberalism and Value Pluralism

Value pluralism is the idea that there are many different “values,” each separate and different, and none truer or more important than the others. Values can be moral (such as a commitment to veganism or gun rights) or non-moral (such as a penchant for physical fitness or botany). Pluralism can be contrasted with “value monism,” which states that there is an objective ranking of values, or perhaps even a single value, which all humans must follow.

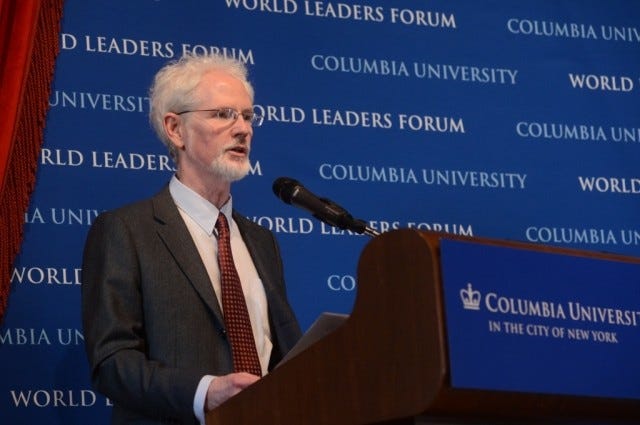

This post examines how pluralism infects liberalism. As a case study, I will examine the liberal theory of David Johnston, a political science professor at Columbia University, in his 1994 book The Idea of a Liberal Political Theory.[1] Johnston appeals to moral value pluralism to justify a state which remains “neutral” between competing moral values. Given the plurality of values, the state’s role is to provide people with the means to pursue their own self-chosen values—not to cultivate healthy or virtuous human beings. However, liberal pluralism ironically produces hostility towards allegedly “illiberal” values. The only sets of values that cannot be tolerated are those which reject the idea that people should be free to set their own values. Johnston ends up arguing for political and social pressure to be placed on people who adopt traditional views of sex, for instance.[2]

David Johnston’s Liberalism

David Johnston’s definition of “philosophical liberalism” has three parts.[3]

Only individuals count

Everybody counts equally

Everybody counts as an agent

The first principle excludes political theories that, say, prioritize the glory of the nation, or the production of philosophy or truth, regardless of their effects on the individuals composing the nation. Liberalism is thus individualist. Johnston claims that the second principle rules out political arrangements which distribute unequal political power to different people, such as aristocracy or monarchy. (I disagree, but I won’t explore that here.)

The third principle is the most important for our purposes given that the concept of “agency” lies at the heart of Johnston’s value pluralism. Johnston defines an “agent” a “being who is capable of conceiving values and projects, including projects whose fulfillment may not be within the range of that being’s immediate experience” (22). In contrast to a mere “sentient being,” who acts only on impulse or in response to its immediate environment, an “agent” requires higher mental powers such as foresight, planning, and creative imagination. As an example of agency, Johnston imagines a woman who values the colonization of Mars by human beings, even if she herself does not participate in or even witness the colonization.

The fact that human beings are agents lies at the center of Johnston’s liberalism. He grounds his first two principle—that only humans count, and that all humans count equally—on his theory of agency. “Human beings count equally in theories that embody liberal values because they equally can claim to have an interest in realizing their projects and values, in bringing their projects to fruition and in seeing their values embodies in the world” (24). The capacity to devise and pursue projects literally gives human beings their value.[4]

For this reason, the entire political structure should be arranged to facilitate the ability of the citizens to exercise their agency. Human beings, Johnston asserts, “have a generalizable interest in having the means necessary to pursue the project we formulate and to try to realize the values we conceive.”[5] Even liberty and individual rights are valuable only to the extent that they function as means to this end, having no inherent value in themselves (138).

Liberalism and Value Pluralism

Johnston believes that the value of human agency presupposes value pluralism. He states:

A society in which individuals are free—that is, a society whose institutions and practices embody the view that individuals are agents who conceive values and pursue projects—will allow diverse conceptions of the good life to arise and flourish. Liberal societies embody, and liberal theories presuppose, what I shall call the assumption of reasonable value pluralism, the assumption that individual reasonably conceive different and conflicting values. (26)

Later he describes the “assumption of reasonable value pluralism” as a “pragmatic implication of the more fundamental liberal premise that human beings are agents” (137).

His point is murky. The fact that humans are capable of conceiving abstract projects or creating unique values does not imply that these projects or values have equal (or any) worth. Some projects or values may be misguided or harmful; some may be more important than others. It doesn’t help that value pluralism is said to be an “assumption.”

Johnston sees value pluralism as a straightforward implication of the philosophical failure to establish objective moral norms. The “dominant view” in the ancient and medieval periods was that political theories should be tested for their adherence to “objective moral norms,” a view which presupposes that “moral norms exist independently of human consciousness and reflection” (32). In the modern world, however, Johnston asserts that work by moral and political philosophers “has tended to undermine” the “notion of objective moral truths,” such that the theory “no longer possesses the general credibility it once had,” although we “cannot say” it has been “disproved” (32).

That’s all, folks. Johnston brushes away centuries of deep reflection on the nature of truth and morality with a casual reference to academic trends. Philosophers have traditionally articulated complicated theories about the structure of the universe, the purpose of life, and the way in which humans ought to live in light of those truths. Johnston dismisses all of this and instead glorifies subjective “projects” and “values” generated by free agents. But if objective moral norms do not exist, then why shouldn’t we conclude that all projects and values are equally worthless? Why, in other words, does the collapse of moral philosophy lead to celebratory individualism rather than to nihilism?

Johnston’s commitment to value pluralism decisively shapes his liberal theory. Most strikingly, he objects to “perfectionist” liberalism, which disparages external sources of authority (such as religious authority or cultural customs) and seeks to turn everyone into autonomous individuals who continuously create themselves through a process of “critical self-appraisal.” Johnston rejects perfectionist liberalism on the grounds that it is false to believe, as perfectionists do, that more enlightened self-reflection will improve one’s ability to discover truth or moral principles. This belief, he writes, “seems to presuppose that the goodness of things is inherent in those things and that our task as agents is to discover the goodness (or badness) that is already in things. This assumption fails to take seriously the fact that human beings hold a plurality of conceptions of the good” and “value different things in markedly different ways” (91). It is a “mistake” to believe that we can “discover the ‘correct’ value of these things by becoming more competent agents,” i.e. by developing our “capacity for critical self-appraisal,” because “there is no such thing as the correct values of things” (91). The very idea “that only competent agents can measure the value of things,” he scoffs, “rests on an obsolete objectivist conception of value” (91).

This is pure moral relativism. Johnston is saying that we cannot rationally judge between two people’s projects and values, even in theory, because there is no external standard by which to judge the rightness or wrongness of these competing projects and values. On this view, it is futile to try to improve the competence of our choices because all choices are equal—and therefore all agents are equally competent.

Reflective Equilibrium

In fact, Johnston appears to perceive the danger of nihilism and desperately tries to ward off moral relativism. If objective moral norms are unavailable, he argues, then the best “test of moral claims” is to consult one’s intuitions or convictions regarding morality and to devise a political theory that “accounts for” and “organizes” as many of these intuitions as possible, at least once one has deeply considered and compared all available options (33-34). Perhaps, upon reflection, one might tweak a moral principle, or disregard a moral intuition, in order to eliminate discrepancies in one’s worldview. The goal is to come to realize what he calls a “reflective equilibrium,” a stable balance between one’s moral intuitions and one’s moral principles. In lieu of a philosophical argument, then, Johnston appears to base his deep commitment to liberal values—including agency—solely on his own moral feelings.

The methodology of “reflective equilibrium” faces serious problems. It assumes the truth of one’s moral intuitions—at least once they have been properly reflected on and weighed against each other. This move raises the question of whether these intuitions are objective or subjective. If they are objective, then why should we reject the idea of objective moral norms? If they are subjective, then why should they bind all of society? And why should we favor one’s own intuitions over the differing intuitions of other people?

In the end, Johnston backs away even from reflective equilibrium. He concedes that repeatedly surveying, considering, and revising all available ethical positions is too difficult, and that people’s moral intuitions vary too much to create common agreement. Johnston ultimately refuses to defend his liberal principles on a rational basis. Instead, he writes: “I shall assume … that the liberal premises I have outlined … would pass the test of wide and general reflective equilibrium …. I shall not attempt to prove this assumption.”[6] Critics who do not share his implicit faith in liberal principles will find little here to change their minds.

Pluralism and Liberal Intolerance

I want to make one more, very important observation about the role of value pluralism in liberal political theory: value pluralism ironically leads liberals to adopt an openly hostile posture towards persons and theories which, in their view, do not accord sufficient respect to people’s diverse projects and values.

Johnston stresses that all citizens should enjoy not only legal equality but also “acceptance and recognition” from their fellow citizens (157). In other words, everyone ought to affirm that other people are “agents with values they want to realize and projects they would like to pursue,” and that these projects and values are equal to those of everyone else (157). Absent such recognition, legal equality will not be enough to allow everyone to life a full life. Some people, Johnston worries, might fail to appreciate other people’s projects and values sufficiently, and might even criticize others’ life choices. Such judgmental behavior causes the targets of criticism to lose “self-respect” and even makes it impossible for them “to participate fully as equals in the public life of their society,” despite enjoying legal equality (157-158).

It follows, of course, that purportedly “illiberal” people and viewpoints must be eradicated, perhaps by government force or perhaps by cultural strangulation, to make room for “public recognition” of society’s full diversity. Johnston does admit that the “state” is not capable of easily “manipulating” the “distribution of status and recognition” in the same way that it can redistribute wealth (158). But he believes that we should strive, as a society, to remove attitudes inimical to people’s “self-respect.” He explicitly mentions racism and sexism as examples. (He defines sexism to encompass any belief in differential sex roles, and considers even women with traditionalist beliefs to be sexist.) And, given his emphasis on individualistic self-creation, he would surely be an enthusiastic opponent of “homophobia” and “transphobia” were he writing today.

We can see, then, that the hostility of contemporary liberals towards traditional worldviews, such as Christian sexual ethics or longstanding distinctions between men and women, is a feature and not a bug of liberalism. Relativistic forms of liberalism lead almost inevitably to intolerance towards anything that allegedly impedes or disparages someone’s free choices. No limits.

Value Pluralism and Postliberalism

This analysis should inform postliberal politics in two ways.

First, postliberals must consider the close connection between state neutrality, value pluralism, and relativism. The declaration that the state will remain neutral between different ethical codes inexorably seems to lead, in practice, to a version of moral relativism in which the only sin is to “judge” others’ choices. Postliberals should reject “neutrality” and boldly declare their commitment to a substantive moral theory as the groundwork for politics. This position does not entail that dissenters should be punished in any way. It is more symbolic than effectual. But symbols matter.

Second, postliberals ought to recapture a more vigorous sense of “liberty.” Liberalism sees liberty as contentless—the freedom to choose one’s own (undefined) “projects and values.” If all “projects and values” are equal, however, then the only sin is attempting to impose a hierarchy of values on others or to interfere with their own “projects and values.” And the only task for politics is to protect people’s ability to act as free choosers.

The classical tradition, by contrast, understands liberty to be the condition of being free to pursue what is right and good. (This can be seen, for instance, in John Winthrop’s “Little Speech on Liberty,” about which I plan to write a Postliberal Primer essay.) Classical thinkers believe, like Johnston, that liberty is only valuable as a means to a greater end. But, the former view liberty as a means to virtue and human flourishing, rather than to a relativistic “agency.”

Too often, conservatives adopt “neutrality” or appeal to a libertarian (i.e. liberal) view of liberty on issues such as vaccine mandates, free speech, or gun rights. By further entrenching liberal values, this move hurts more than it helps. Postliberal conservatism can only begin when we cease accommodating, triangulating, or doubling down on the reigning orthodoxy.

[1] https://polisci.columbia.edu/content/david-c-johnston.

[2] I am using “sex” in place of the more popular term “gender.”

[3] David Johnston, The Idea of a Liberal Political Theory (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 18-24. All parenthetical citations are to page numbers in this book.

[4] Johnston does not directly address the status of humans who are unable, due to intellectual disabilities or youth, to form and pursue projects and values. He implicitly assumes that non-agent humans are equally valuable as everyone else, since he believes that it is very important to develop the ability of all humans to be agents. But if human value or worth is dependent on agency, then why should human non-agents have rights or dignity?

[5] Johnston, The Idea of a Liberal Political Theory, 137-138. Emphasis in original.

[6] Ibid., at 39.

It would seem Johnston is latter day Emersonian. The Frogpondians are with us still.