Does the Prevalence of Infanticide Provide Support for Abortion?

Refuting an Evolutionary Argument for Abortion

Is the structure of human nature relevant to morality? This post applies my earlier analysis of worldviews to a specific policy debate. My schema can help to reveal erroneous argument popular in political debates.

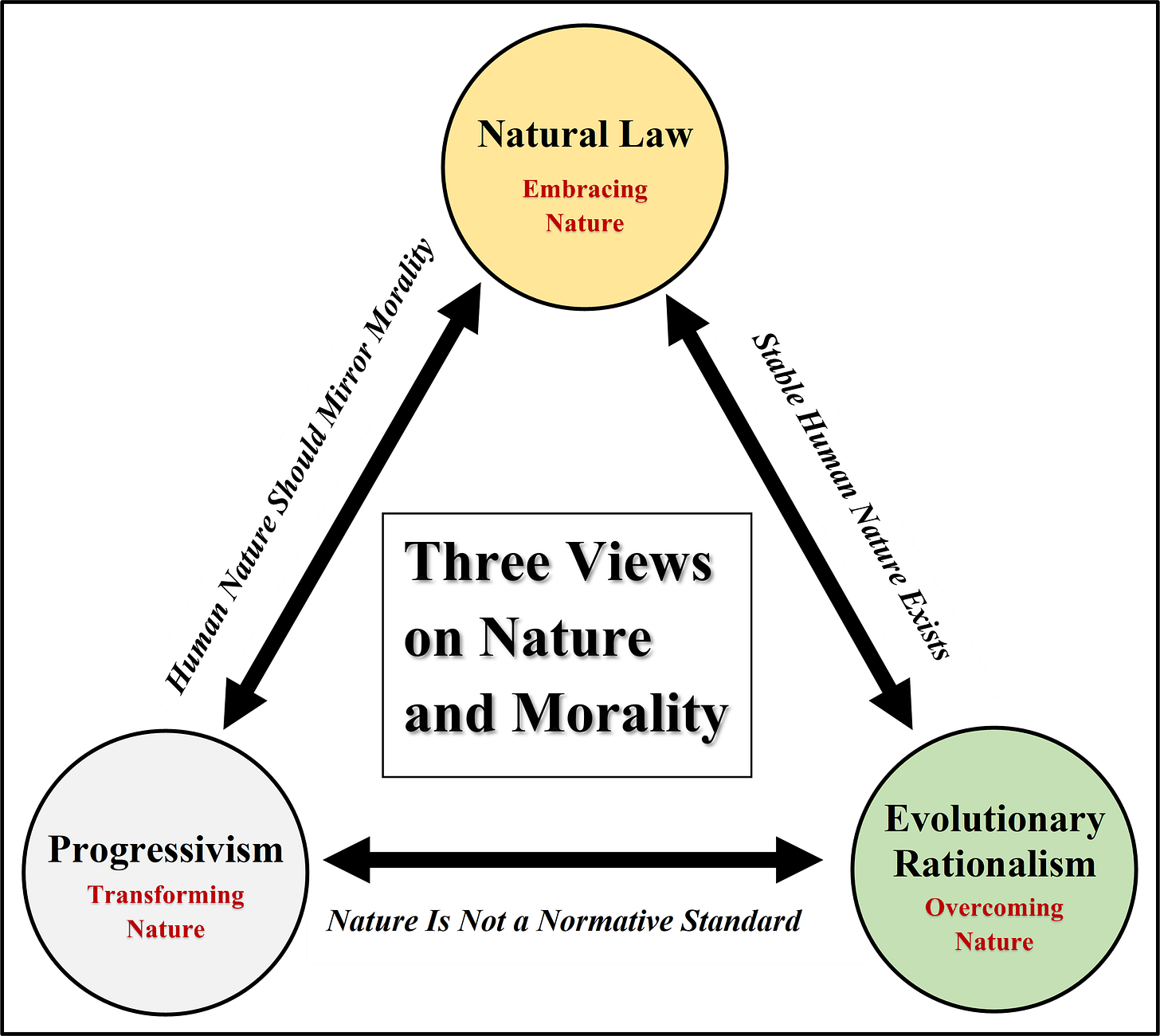

In earlier work, I compared and contrasted the three worldviews that dominate our society: natural law, progressivism, and evolutionary rationalism. Each “worldview” is a broad outlook that encompasses many specific views. Yet each worldview agrees with two of the following three claims:

A stable human nature exists.

Human nature should mirror morality.

Nature is not a normative standard for moral behavior.

The “evolutionary rationalist” worldview, which is most relevant to this post, adheres to propositions 1 and 3. On this view, nature is not socially constructed but also does not provide a pattern for human behavior. I would recommend reading (or re-reading) this essay before proceeding.

This post deploys my worldview schema to critique an “evolutionary” argument for abortion. In Quillette, Rob Brooks writes about infanticide and its relation to the abortion debate. He defends abortion on the grounds that a desire to abort one’s child (under certain circumstances) is seemingly embedded within human nature and serves evolutionary purposes. Brooks’ invocation of human nature to buttress his moral argument, I argue, violates the fundamental principles of the “evolutionary rationalist” worldview which he adopts. On this worldview, it is inappropriate to draw a moral conclusion from facts about how humans are wired evolutionarily. In other contexts, in fact, evolutionary rationalists repeatedly and hotly deny any such connection between human nature and morality. However, I conclude that, while Brooks’ argument fails, the evidence he presents ought to trouble adherents of the “natural law” worldview (to which I belong).

Rob Brooks’ Argument

Rob Brooks begins by emphasizing the universality and long history of infanticide. For thousands of years—even before the rise of organized religion, philosophy, or complex political communities—cultures across the world have killed newborn infants. The killing is generally performed by the mother. This pattern is observed in a variety of animal species as well.

From this evidence, Brooks hypothesizes that infanticide serves some evolutionary purpose related to human survival. In particular, animals (including humans) are predisposed naturally to abandon or kill children who are unlikely to survive to adulthood. “When animal mothers kill or abandon their newborn young, they do so because their current circumstances are so poor that rearing those young will not be worthwhile. They can then immediately start feeding and get a chance to breed again under better conditions.” In this way, females can produce more surviving offspring than if they jealously guarded all of their children no matter the circumstances. Evidence from human infanticide supports this hypothesis: mothers who kill or abandon their babies are disproportionately young and/or poor and/or unmarried—hardly ideal candidates to raise quality children.

Brooks’ account “debunks” the popular image of the mother as selfless caregiver. The evidence from evolutionary biology, he argues, points to mothers as “strategic investors, sensitive to each child’s chances of thriving, and attuned to their own projected costs of breastfeeding, protecting, and caring for the child over the coming years.” No wonder the popular stereotype of the “evil stepmother” who favors her biological children over her husband’s children with a previous wife.

Abortion serves the same role as infanticide. Studies apparently show that, when denied an abortion, women (and their living children) go on to lead worse lives than similarly situated women who obtained an abortion. Abortions was so rare in the past, according to Brooks, only because it was more dangerous than infanticide. Now that medical advances have made it easier and safer, abortion has become the means of choice for escaping the drudgery of mothering under suboptimal conditions. And, just like infanticide, it turns out that abortion, too, is concentrated in young, single, and/or poor mothers.

Brooke concludes that these factors ought to weigh in favor of abortion. He argues that, given the deeply rooted nature of the desire to avoid motherhood under nonideal circumstances, women will always seek illegal means to kill a fetus or infant if legal means are removed. “Safe abortion,” he writes, “is the modern cure for the ancient heartbreaks of neonaticide and abandonment. Rates of infant death (due to infanticide) have, in fact, been observed to plummet after abortion becomes legal.” He also advocates for contraceptive access as a means to prevent both pregnancy and abortion.

The Problem with Brooks’ Argument

It is not clear whether Brooks expects his essay to be a free-standing defense of abortion, or whether he is merely adding sociological evidence to inform the debate. Yet the tone of the article indicates that he thinks his argument contributes somehow to the pro-choice cause. In this, it fails, because Brooks misunderstands the role of evolutionary thinking in moral arguments.

Allow me to explain why. As I wrote previously, evolutionary rationalists believe that a stable human nature exists, but that humans cannot draw conclusions about morality from the structure of human nature. In other words, nature is not a normative standard for moral behavior. On the evolutionary rationalist account, morality arises out of an (unknown) process distinct from evolution. It exists outside of the natural world, which is thoroughly materialistic.

The greatest example of this is the fact that, evolutionarily speaking, the primary goal of all organisms is to survive and perpetuate their genes. These goals, and especially the second one of reproduction, are not generally seen as moral aims. Most people are morally indifferent—and believe that everyone should be morally indifferent—to whether or not someone reproduces. (Being morally indifferent is not same as being emotionally indifferent. One may want children but not regard it as a moral imperative to have children.)

To be sure, evolutionary thinking may be relevant to moral debates when the latter hinge on whether or not there is a stable human nature. Some, for instance, invoke rationalist arguments to deny that people can change their sex, or to argue that sex differences are not socially constructed. Both issues obviously relate to contemporary moral debates over transgenderism and feminism. For instance, if there are hardwired biological differences between males and females, then that fact that men and women choose different career paths may be “natural” and not the result of subtle sexism—as what I call the “progressive” worldview holds.

However, evolutionary rationalists believe that one should not say that humans ought to follow their nature or that their nature leads humans towards their good. So, for instance, one ought not to conclude that men and women have different roles just because there are, on average, sex differences between males and females, for it is a moral principle that everyone is equal and thus has the same role.

Applying this position to abortion, then, it ought to be morally irrelevant, for the evolutionary rationalist, whether or not infanticide is widespread or “natural.” The fact that non-human animals and most human societies practice infanticide says nothing about its moral value. All of the evidence produced by Brooks is simply irrelevant; the debate over abortion must take place on other grounds. And if it turns out that abortion is wrong, then the fact that people can be expected to resist abortion restrictions does not imply that such restrictions are wrong. People resist laws they dislike all the time.

Brooks could, of course, bite the bullet and argue that nature provides a normative pattern for human behavior after all. But then he would be faced with the problem that there are many abominable, yet widespread, cultural practices designed to perpetuate the genes of a person or group. One might think of rape, or offensive warfare, along with cultural attitudes such as tribalism. Much of human history is the story of groups of people working together to destroy or dominate another group of people in order to survive or grow. Brooks probably doesn’t want to go this route.

How Infanticide is a Problem for Natural Lawyers

If the evolutionary account of morality is deficient, adherents to the worldview I term “natural law” face a problem of their own. Natural law theory views nature as a normative model for human behavior. Universal patterns of behavior are seen to indicate the will of God. As Richard Hooker writes: “The general and perpetual voice of mankind is as the judgment of God Himself, since what all men at all times have come to believe must have been taught to them by Nature, and since God is Nature’s author, her voice is merely His instrument.”

For natural law theorists, then, the ubiquity of infanticide across human cultures poses a challenge. It seems “natural” to kill babies—at least in the sense that lots of people have considered it morally acceptable. So isn’t it God’s will?

There are ways to explain discrepancies between what seems to be moral (“do not kill”) and longstanding customs. Since the dawn of philosophy in ancient Greek, if not before, people have been well aware that different cultures practice different customs, and that some of these customs are evil. Natural lawyers have developed several explanations for evil customs. Sometimes, people are too lazy or too vain to make the effort to understand their faults, and people can also err by misapplying clear principles of natural law to specific subjects. Some evil customs, like witch burning, are based on false empirical beliefs deriving from superstitions or bad science. Perhaps the most compelling answer is that human nature is, in some sense, corrupted—what Christian call “original sin.” But this teaching, however obvious it may seem, is known from Scripture and not directly from natural reason.

I think the strongest argument against infanticide is that it has not been universally embraced. One possible indication of people’s moral qualms about infanticide is that mothers would usually abandon their infants to die of exposure rather than kill them directly. Many societies only kill “deformed” infants who may have trouble surviving anyway. Most importantly, many cultures have not practiced infanticide at all. The Old Testament praises fertility and deplores the practice of sacrificing infants to pagan gods, and Jewish culture has opposed infanticide. Most notably, Christianity from the first opposed the infanticide widespread in the Roman Empire, Many Christians rescued babies abandoned by Pagan Romans and raised them as their own, and churches began to provide orphanages to house abandoned children. Muslim societies, too, prohibit infanticide. In fact, the Qu’ran directly states: “slay not your children because of penury – we provide for you and for them … slay not the life which Allah hath made sacred” (Surah 6, verse 151). However understandable infanticide may seem in ages of desperate poverty, it does not follow that it accords with natural law.

Conclusion

Neither evolutionary rationalists nor natural law theorists have a perfectly compelling answer to the problem of infanticide/abortion. For the former, it is impossible to make the leap from the fact that abortion is a widespread custom to the normative claim that abortion is morally acceptable. For the latter, a tension lingers between the belief that nature supplies a standard of behavior and the fact that human appear to be predisposed to kill their offspring. The evidence provided by Brooks ought to compel natural law theorists to devise more sophisticated responses to the problem of widespread cultural evil.

In the end, however, I think the problem is worse—indeed, insurmountable—for the evolutionary rationalist. Given that nearly everyone (except Peter Singer) agrees that infanticide is wrong, they would have to endorse the exposure or killing of unwanted children in order to be consistent in their moral argumentation. That’s a hard pill to swallow. Even Brooks refrains from endorsing infanticide explicitly. And, assuming for the moment that abortion is morally equivalent to infanticide (as pro-life people do), it follows that they ought to be treated the same way, regardless of cultural views on the matter. In both cases, the purpose of the killing, from an evolutionary perspective, is to enable a woman to better perpetuate her genes. No one regards this goal as moral or acceptable in itself. The evolutionary argument for abortion, then, fails.